In a Western society such as ours, it is a peculiar mission – to restore mauri to a natural resource. However, from a Māori perspective, this is a perfectly normal and noble mission. The time has come to approach environmental issues from a different perspective.

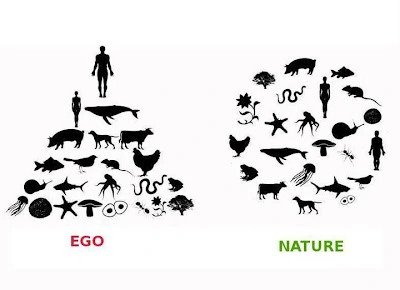

Western science and Indigenous cosmology suggest two very different ways of thinking about the world. The Enlightenment mind-set, favoured by European societies, see humans as separate and dominant over nature. Like Indigenous people around the world, Māori share a belief in the inseparable relationship that exists between people, nature and the cosmos.

As Kennedy Warne, Editor-at-Large for New Zealand Geographic, explains it: “Where European ontology [the nature of being] is linear and hierarchical, Māori ontology is circular and reciprocal. European thinking leads to separation and objectification; Māori thinking leads to relational exchange — ‘the rhizomatic, ramifying networks of whakapapa’ as Dame Anne Salmond describes it. If the Enlightenment view is epitomised in ‘I think therefore I am’, the Māori understanding is ‘I relate therefore I am’.” Māori make sense of the world through how things relate and connect.

Western Enlightenment and Indigenous truths are so inherently different that it is often thought they cannot coexist in a modern, western society. But in New Zealand they can, and finding more intersections where perspectives meet could hold the key to both nature and people flourishing.

Nature IS an ancestor.

The best way to understand how nature, people and the cosmos are connected is through whakapapa – our genealogical relationships. So the interesting thing about whakapapa is that it extends beyond human relationships. As Charles Royal explains, “the natural world from a Māori perspective, forms a cosmic family, the weather, birds, fish and trees are related to each other, and to the people of the land”.

This is the lineage that reflects the creation narratives of Sky-Father Ranginui and Earth-Mother Papatūānuku. From the chaos of their violent separation, the darkness receded and the world of light emerged. The elements, the atmosphere, the water, the forests, the birds, the people were brought to life - all descendants of the divine, all created out of the same dust. This is how these narratives relate people to mountains, rivers, trees, and even birds as a part of a larger extended family. This way of relating the individual and the natural world strengthens the bond between them, and just like human relationships, it guides the interactions and behaviours that ensure mutually beneficial outcomes.

A good example of how this Indigenous truth coexists within a Western framework is the Te Urewera Act 2014. Tuhoe people see the Te Urewera forest in the eastern Bay of Plenty as their living ancestor. Known as Children of the Mist, they were brought forth from Maungapōhatu (the Mountain) and Hine-pūkohu-rangi (the Mist Maiden). They are of the forest and they are the forest – it’s their shared identity. In a world first, New Zealand has recognised that relationship with legislation, and granted Te Urewera its own identity. Section 3 of the Te Urewera Act 2014 reads:

Te Urewera is ancient and enduring, a fortress of nature, alive with history; its scenery is abundant with mystery, adventure, and remote beauty.

Te Urewera is a place of spiritual value, with its own mana and mauri.

Te Urewera has an identity in and of itself, inspiring people to commit to its care.

Te Urewera Forest is recognised as a sentient being, a living ancestor “inspiring people to commit to its care”. The Tuhoe people benefit, Te Urewera benefits. Sustainability is a key focus for this iwi, with their living, green buildings and business ventures which benefit both people and nature.

We share the same energy – we are the same.

Within the 2014 Te Urewera legislation, the Māori concepts of mauri and mana are mentioned.

Mana refers to an extraordinary power, essence, presence, and charisma. It is ever-present energy and applies to people, the cosmos and the natural world. When this super-natural force is allowed to flow, all life is enhanced and invigorated. Without mauri/life force however, mana cannot flow into a person or object.

Mauri is the life energy which binds and animates all things in the physical world. Without mauri, or life essence, mana cannot flow into a person or object. The actions we take can enhance or diminish mauri in the same way caring for our health enhances it and neglecting our health, degrades it.

In breaking down the word, we may get a deeper understanding of it.

Ma = To be connected to, bound to, linked to, joined to

Uri = Descendants. All things, seen and unseen

The important point here is the connectedness of all things, in seen and unseen, obvious and obscure ways. Each ripples out and affects the other. If the land, or a body of water has no mauri – life force, it cannot have mana – power and energy. If the water is sick, it is a direct reflection of the people inextricably linked through whakapapa. As Waikato senior law lecturer Linda Te Aho explains: “We see ourselves as not only of the land but as the land.”

Heal the environment, heal ourselves.

Personification of the natural world is a key component of Māori and other indigenous cultures around the world. This kind of thinking allows direct communication with nature and through observing its workings, we can find clues to heal ourselves and the parts of society that need it. As Māori rongoa [medicine, healing] practitioner Donna Kerridge explains, “Learn to heal the bark of a tree, learn to heal skin. When experiencing the breakdown of communities, look to the diversity and order within healthy forest communities for the answers. When the importance of wetlands and their role in cleaning water is understood, it is possible to appreciate the work of kidneys in the human body”.

Pressing issues like water quality and climate change are affecting us all. While Western science has an important role to play, it has yet to create the momentum needed for the masses to catch on - to want to commit to the care of the environment. Imagine for two minutes, if the Indigenous worldview was also widely accepted. What if we all saw that coastline, river or mountain as a direct reflection of ourselves? Would we be so careless as to degrade it with our rubbish? Would we take from it and use it all up until it is depleted and can no longer support life? Or, would we be a little more mindful, careful and caring?

Finding these small intersections, the places where Western science and Indigenous truths collide, holds the key to people and nature prospering. Here at SBN we have one such intersection. As mentioned earlier, one of our major projects this year is GulfX. Together with businesses and like-minded people, SBN is working to restore the mauri of this body of water. Everything has mauri, a vitality or essence that supports life. We all have the power to enhance the mauri of our waterways, and we have the power to diminish it. The way to enhance mauri is to clean up the rubbish, sediment and micro plastics in the water, and work on ways that keep these land-based pollutants out of the water altogether.

Mauri in this instance is about the health of the water and the relationship [whakapapa] between water, environment and people. We want to actively support a future where this body of water can be the playground and the food cupboard for all New Zealanders – who, in return, will commit to its care. Restoring the mauri of this waterway enhances mana, power and vitality –the Hauraki Gulf is a virtual wellspring for our largest city. GulfX opens an opportunity for people and businesses to join the conversation, and collaborate on fresh ideas as to how to protect and enhance the mauri of this water.

If you want to find out more about our mission to restore the mauri of the Hauraki Gulf, you can find out more here. It’s FREE and we strongly encourage you to join us- there’s a list of things you can do to help right now.